Where The Blue Line Ends... (Part 1)

With the approach of the bicentennial

of the first spadefuls of dirt turned in constructing the Erie Canal, it may be of interest to

explore a bit about the early survey work and the eventual canal construction

in the area that is now part of Schoharie

Crossing State Historic Site. What

was not a given at the time, was the path of the canal from the Schoharie Creek

to Albany. When they broke ground on July

4th 1817 in Rome, the canal “blue line”

ended at the banks of the Schoharie.

Running a canal through the

Mohawk Valley was by no means a new concept.

Going back to the colonial era under the then surveyor general Cadwallader

Colden, it was noted as a potential global improvement and prudent endeavor

for British colonial rule of the continent to at least improve inland

navigation. Travelers for decades

between then and the early 1800’s had noted the geological advantages of the Mohawk Valley – even George

Washington thought it a great concept, though never would have approved of federal monies to pay for a canal.

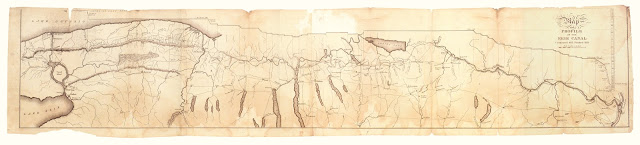

After a long process of gaining legislative approval for funding, in 1816, Charles

Brodhead had been assigned to survey the route from Rome, NY to the Schoharie Creek. The continuation to Albany would not be

settled until the last possible moments before the construction of that fifty

mile section. Brodhead had a long

surveying past, even ascending an Adirondack high peak in the 1790’s, before establishing

himself in the Utica, NY business world.

Several years pasted before he then heeded the call to Erie work. Brodhead

returned to central NY before the completion of the canal and did not advance

into the history books with those surveyors turned engineers.

As author and historian Gerard

Koeppel notes in his work Bond of Union, that stretch of the

Mohawk Valley that Brodhead was to tasked to survey was already “a region of

merchants, travelers, and crude boatmen, raucous riverside taverns and public

houses, with the comforts and discomforts

of rough progress” (emphasis added). It

also encompassed many of the most difficult elevation changes of the entire

canal route. Brodhead’s character and

experience aligned perfectly for such a task.

Within the company of men

assigned to execute that survey was Canvass

White – noted predominately now in canal lore as not just a surveyor or

engineer but the savior of the project in its earliest stages for his reported

“discovery” of a particular

limestone in NY and the process by which to transform it into hydraulic cement. That cement was necessary to build locks,

culverts and other canal masonry.

With the foolish idea of the

incline plane canal put aside (which would have required an elevated canal

prism 150 feet higher than the Schoharie Creek) the survey would necessitate

the canal to traverse the creek and overcome the elevation changes that occur

across the section and most precipitously toward Albany.

|

| John Jervis Oneida County Historical Society |

The former ax-man, John Jarvis

was the engineer in charge of the Erie Canal division from Anthony’s Nose to Amsterdam when the 1821 construction

season began. While the section required

four locks, the most daunting task may have involved the crossing through the

Schoharie Creek. Any ease Jarvis

experienced, was gained in this division - according to Koeppel, entirely due to

the previous oversight and contracting of Canvass White. Further oversight of Jarvis by Chief Engineer

Benjamin Wright and

Canal Commissioner Henry Seymour

would provide guidance to build his confidence as the canal inched eastward. And although his section would leak and need

vast repairs in 1822, it was indicative of the nature and conditions of canal

construction through the eastern sections of the Grand Canal – the difficulty

of traversing a region full of “Flood-prone Streams,” need for aqueducts and

the difficult south bank of the Mohawk

River that required the construction of dams, guard locks and culverts.

|

| Henry Seymour |

The Schoharie Creek was vital in

the hydraulic system of the Erie Canal

even in 1822. It was the primary source

of water to the fifty mile stretch from its banks to Albany; A section that

would require large amounts of flow to conduct passage through the nearly two

dozen locks to reach the Hudson River. In

order to facilitate this transference of creek water into the canal – as well

as ease the crossing of its flowing body – a slack

water dam would be constructed and continually maintained in the Schoharie

even up into the era of the early 20th century when the canalized

Mohawk River no longer made use of the creek’s waters in that fashion.

You can discover more on that topic by reading these previous articles:

Comments

Post a Comment